Scientists Think They Found a Way to Boost Your Immune System—and Slow Down Your Aging

While the fabled fountain of youth may not actually exist, a new type of therapy now does.

Everything seems to break down as we age. Besides the almost inevitable creaking joints and random aches, there are a number of things not even a few aspirin can fix. The immune system, unfortunately, is one of those. Immune function declines over time because the production of T-cells decreases, but there might soon be a way to reverse that dropoff.

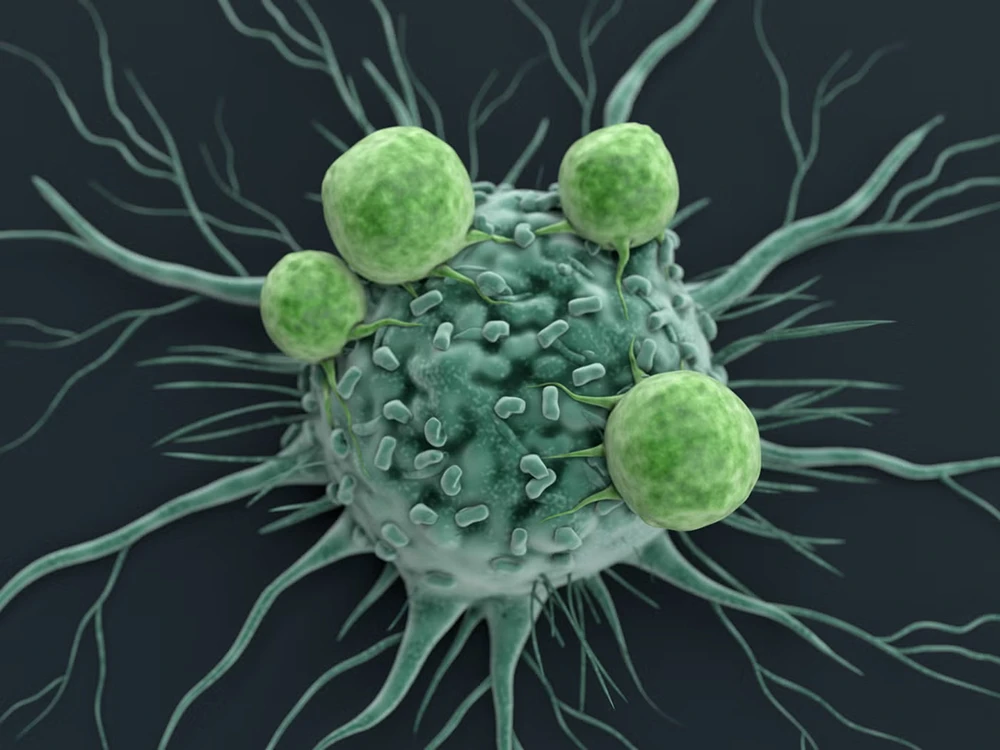

T-cells are produced by the thymus gland, and promote homeostasis in the immune system, adapting to fight everything from allergens to pathogens and tumors. As thymus function declines with age, the gland shrinks and releases fewer T-cells, which are prone to dysfunction and not as capable of quickly reacting to pathogens and other threats. Now, an MIT research team led by neuroscientist Feng Zhang has found a way to reboot the immune system by recreating the thymus signals that stimulate T-cells.

“We found that [our] approach significantly improved immune response in aging mice in both vaccination and cancer immunotherapy models with no adverse side effects or evidence of increased autoimmunity,” Zhang said in a study recently published in the journal Nature. “These results highlight the potential of this approach to improve immune function and, more broadly, to use the liver as a transient ‘factory’ for replenishing factors that decline with age.”

Previous attempts at creating an immune fountain of youth have been unreliable, either falling short of being effective enough, not being clinically viable, or even turning out to be toxic. So, Zhang decided to flip a few genetic switches. He and his team worked with older mice whose immune systems were not what they used to be, and after identifying which proteins act as signaling pathways that help T-cells mature and differentiate, they injected the mice with messenger RNA (mRNA) that encodes those three pathways.

The target for the mRNA was protein synthesis in the liver, as it continues at high levels even with advanced age. The mRNA was carried there by lipid nanoparticles, and once these particles accumulated in the liver, hepatocytes (liver cells) began to create them. This allowed Zhang’s team to essentially use the liver as a temporary manufacturing plant for T-cells. Treatments in mice increased both the amount and frequency of new T-cells that were ready to be activated, and with about a month of treatment, there were only minimal side effects.